Where Is The Dna In An Animal Cell

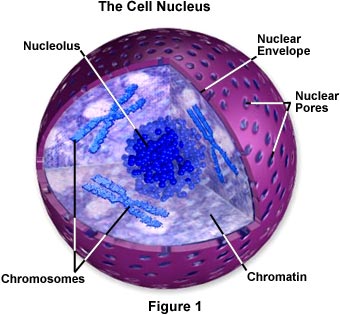

Creature Cell Nucleus

The nucleus is a highly specialized organelle that serves as the data and administrative center of the prison cell. This organelle has two major functions. Information technology stores the jail cell's hereditary fabric, or DNA, and information technology coordinates the cell's activities, which include intermediary metabolism, growth, poly peptide synthesis, and reproduction (cell division).

Only the cells of avant-garde organisms, known every bit eukaryotes, take a nucleus. By and large in that location is simply one nucleus per cell, but at that place are exceptions such as slime molds and the Siphonales grouping of algae. Simpler ane-celled organisms (prokaryotes), like the bacteria and blue-green alga, don't have a nucleus. In these organisms, all the cell's information and administrative functions are dispersed throughout the cytoplasm.

The spherical nucleus occupies about x percent of a prison cell's book, making information technology the prison cell's near prominent feature. Most of the nuclear material consists of chromatin, the unstructured form of the cell'southward Deoxyribonucleic acid that will organize to form chromosomes during mitosis or cell sectionalization. Also inside the nucleus is the nucleolus, an organelle that synthesizes poly peptide-producing macromolecular assemblies called ribosomes.

A double-layered membrane, the nuclear envelope, separates contents of the nucleus from the cellular cytoplasm. The envelope is riddled with holes called nuclear pores that allow specific types and sizes of molecules to laissez passer dorsum and along between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. It is also fastened to a network of tubules, called the endoplasmic reticulum, where protein synthesis occurs. These tubules extend throughout the cell and industry the biochemical products that a particular cell type is genetically coded to produce.

-

Chromatin/Chromosomes - Packed inside the nucleus of every human cell is nearly 6 feet of Dna, which is divided into 46 individual molecules, one for each chromosome and each about one.5 inches long. Packing all this cloth into a microscopic cell nucleus is an extraordinary feat of packaging. For DNA to function, it can't exist crammed into the nucleus like a ball of string. Instead, it is combined with proteins and organized into a precise, meaty structure, a dense string-like fiber chosen chromatin.

Each Deoxyribonucleic acid strand wraps effectually groups of pocket-size protein molecules chosen histones, forming a series of bead-like structures, called nucleosomes, connected by the DNA strand. Nether the microscope, uncondensed chromatin has a "beads on a string" appearance.

The string of nucleosomes, already compacted past a factor of half-dozen, is so coiled into an even denser structure, compacting the DNA by a factor of 40. This compression and structuring of DNA serves several functions. The overall negative charge of the DNA is neutralized past the positive accuse of the histone molecules, the DNA takes up much less space, and inactive Dna can be folded into inaccessible locations until it is needed.

In that location are 2 types of chromatin. Euchromatin is the genetically active portion and is involved in transcribing RNA to produce proteins used in cell role and growth. Heterochromatin contains inactive Dna and is the portion of chromatin that is most condensed, since it not being used.

Throughout the life of a cell, chromatin fibers take on dissimilar forms within the nucleus. During interphase, when the jail cell is carrying out its normal functions, the chromatin is dispersed throughout the nucleus in what appears to be a tangle of fibers. This exposes the euchromatin and makes it available for the transcription procedure.

When the cell enters metaphase and prepares to divide, the chromatin changes dramatically. First, all the chromatin strands make copies of themselves through the process of Dna replication. Then they are compressed to an even greater degree than at interphase, a 10,000-fold compaction, into specialized structures for reproduction, termed chromosomes. As the jail cell divides to become 2 cells, the chromosomes separate, giving each cell a complete copy of the genetic data contained in the chromatin.

-

Nucleolus - The nucleolus is a membrane-less organelle within the nucleus that manufactures ribosomes, the cell's protein-producing structures. Through the microscope, the nucleolus looks like a large dark spot within the nucleus. A nucleus may contain up to 4 nucleoli, but within each species the number of nucleoli is fixed. Subsequently a jail cell divides, a nucleolus is formed when chromosomes are brought together into nucleolar organizing regions. During cell division, the nucleolus disappears. Some studies suggest that the nucleolus may be involved with cellular aging and, therefore, may touch the aging of an organism.

-

Nuclear Envelope - The nuclear envelope is a double-layered membrane that encloses the contents of the nucleus during near of the prison cell's lifecycle. The space between the layers is called the perinuclear infinite and appears to connect with the rough endoplasmic reticulum. The envelope is perforated with tiny holes called nuclear pores. These pores regulate the passage of molecules between the nucleus and cytoplasm, permitting some to pass through the membrane, but not others. The inner surface has a protein lining called the nuclear lamina, which binds to chromatin and other nuclear components. During mitosis, or jail cell sectionalisation, the nuclear envelope disintegrates, just reforms as the two cells consummate their germination and the chromatin begins to unravel and disperse.

-

Nuclear Pores - The nuclear envelope is perforated with holes called nuclear pores. These pores regulate the passage of molecules between the nucleus and cytoplasm, permitting some to pass through the membrane, but not others. Building blocks for building DNA and RNA are allowed into the nucleus as well as molecules that provide the free energy for constructing genetic fabric.

The pores are fully permeable to small-scale molecules up to the size of the smallest proteins, but course a barrier keeping most large molecules out of the nucleus. Some larger proteins, such as histones, are given admittance into the nucleus. Each pore is surrounded by an elaborate poly peptide structure called the nuclear pore complex, which probably selects large molecules for entrance into the nucleus.

BACK TO ANIMAL Jail cell STRUCTURE

Questions or comments? Transport united states of america an email.

© 1995-2022 by Michael W. Davidson and The Florida State Academy. All Rights Reserved. No images, graphics, software, scripts, or applets may be reproduced or used in any fashion without permission from the copyright holders. Utilise of this website ways you agree to all of the Legal Terms and Atmospheric condition set forth past the owners.

This website is maintained by our

Graphics & Web Programming Team

in collaboration with Optical Microscopy at the

National Loftier Magnetic Field Laboratory.

Last modification: Friday, Nov 13, 2015 at 02:18 PM

Admission Count Since October 1, 2000: 543688

Microscopes provided past:

Source: https://micro.magnet.fsu.edu/cells/animals/nucleus.html

Posted by: merrittjohor1987.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Where Is The Dna In An Animal Cell"

Post a Comment